How Federal Funding Impacts Affordable Housing in Lancaster County

By Tim Stuhldreher in partnership with The Lancaster County Community Foundation

June 16, 2025

Our unique role as a community foundation allows us to hear directly from organizations on the front lines to learn first hand how federal actions are impacting us here in Lancaster County. To help connect our shared community with accurate information, we reached out to a variety of organizations to understand how cuts to federal support may impact housing and homelessness throughout Lancaster County.

While our community has made meaningful progress in caring for our neighbors without permanent housing, Lancaster County’s resources for homeless and at-risk populations are already stretched thin, local leaders say.

The end of COVID-era aid “has left deficits in the community and is increasing needs beyond service providers’ capacities,” the Lancaster County Redevelopment Authority and the county Homelessness Coalition said in their draft 2025 action plan.

“Programs are saturated at their current state,” Deb Jones, who leads the coalition’s office at the authority, told her audience at an Hourglass Foundation forum last year. “The system needs to be expanded.”

Instead, it could be stretched even thinner if Congress enacts the budget cuts and program changes that the current administration is proposing for the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development. The result could be higher local housing costs and more people living in their cars or on the street, advocates warn.

“We’re worried,” said Jake Thorsen, chief impact officer of Tenfold, which provides a range of services around housing and household financial stability. Nonprofits like his operate on tight budgets, Thorsen said: Pare back funding even modestly and “it gets very challenging very quickly.”

The administration’s proposals are contained in its “skinny budget” for fiscal 2026, released in early May, and the detailed follow-up document put out a few weeks later. (The federal FY2026 begins later this year, on Oct. 1.)

The budget proposes cutting HUD funding by 44%, from $77 billion to $43.5 billion. Numerous programs would be slashed and shifted to the states as block grants. Some would be eliminated altogether.

The administration says state and local governments are better positioned to solve housing issues. It says federal housing dollars funded “the harmful woke, Marxist agenda” and that fair housing programs “waged war on America’s suburbs.”

The president’s budget is just the first step in a long negotiation process, said Justin Eby and Deb Jones, the executive director of the Lancaster County Redevelopment Authority and the director of the Office of the county Homelessness Coalition, respectively. It is Congress, not the president, that enacts budget legislation. Previous administrations have proposed cuts, too, they noted; it’s “way too early” to speculate on the potential impact on Lancaster County, Eby said.

The federal budget is currently working its way through the Congressional budget process with an uncertain outcome.

Local nonprofit leaders said they are sketching out contingency plans as best they can amid the uncertainty. Tenfold’s fiscal year starts July 1: drafting a budget in the current level of uncertainty is “really challenging,” Thorsen said.

Water Street Mission, Lancaster County’s largest housing services nonprofit, does not accept federal dollars, relying on private giving. But it collaborates with many that do, and spokesman Matt Clement said the organization recognizes the importance of HUD funding to their budgets and the community-wide challenge the proposed cuts would produce.

“We definitely have an uphill battle that we’re going to have to face together,” he said.

The remainder of this article opens with a brief look at the state of housing in Lancaster County. It then explores several aspects of the administration’s proposals for HUD and how each could play out here. It closes with a discussion of whether federal housing assistance is needed at all.

Is there a housing crisis in Lancaster County?

In a word, yes. Like communities nationwide, Lancaster County has been struggling with rising housing costs and increased homelessness, especially since the pandemic. The issue has prompted community meetings, official hearings, deliberative forums and a county strategic plan, now in development.

Here’s what the data says:

Supply, demand and housing cost burdens

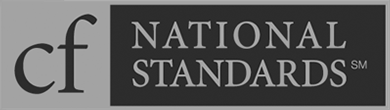

According to U.S. Census data, median incomes in Lancaster County rose about 10% between the periods 2012-16 and 2017-21, while median home prices increased 20%. As of 2022, the local ratio of home prices to annual income was just under 4.0, a local record, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University. Since then, home sale prices have climbed another 15% or so, according to the Lancaster County Association of Realtors’ monthly statistical reports.

As for the rental market, the local vacancy rate is among the lowest in the U.S. As of 2023, the most recent data available from the U.S. Census, it remained at a skimpy 3.4%. That gives landlords pricing power, and keeps rents high. Median rent in the county that year was $1,329, up 27% from 2019.

The problem is especially acute at the lower end of the market. In 2022, the county redevelopment authority estimated that Lancaster County had a shortage of 18,500 units affordable to households making less than 50% of county median income (currently $41,500 for a family of four).

A tight housing supply increases the likelihood that households will be cost-burdened, spending more than 30% of their income to keep a roof over their heads. That leaves them less money to cover their other expenses and put toward savings and puts them at higher risk of insolvency and eviction. Indeed, cost of living is “the primary driver of homelessness,” according to a 2023 University of Washington study.

Countywide, 42% of rental households are cost-burdened, according to HUD. (For homeowners, the rate is 18%.) Among rental households making less than 50% of median income, the number jumps to more than four out of five. More than a third of the latter households are severely cost burdened, paying more than half their income on housing.

Homelessness

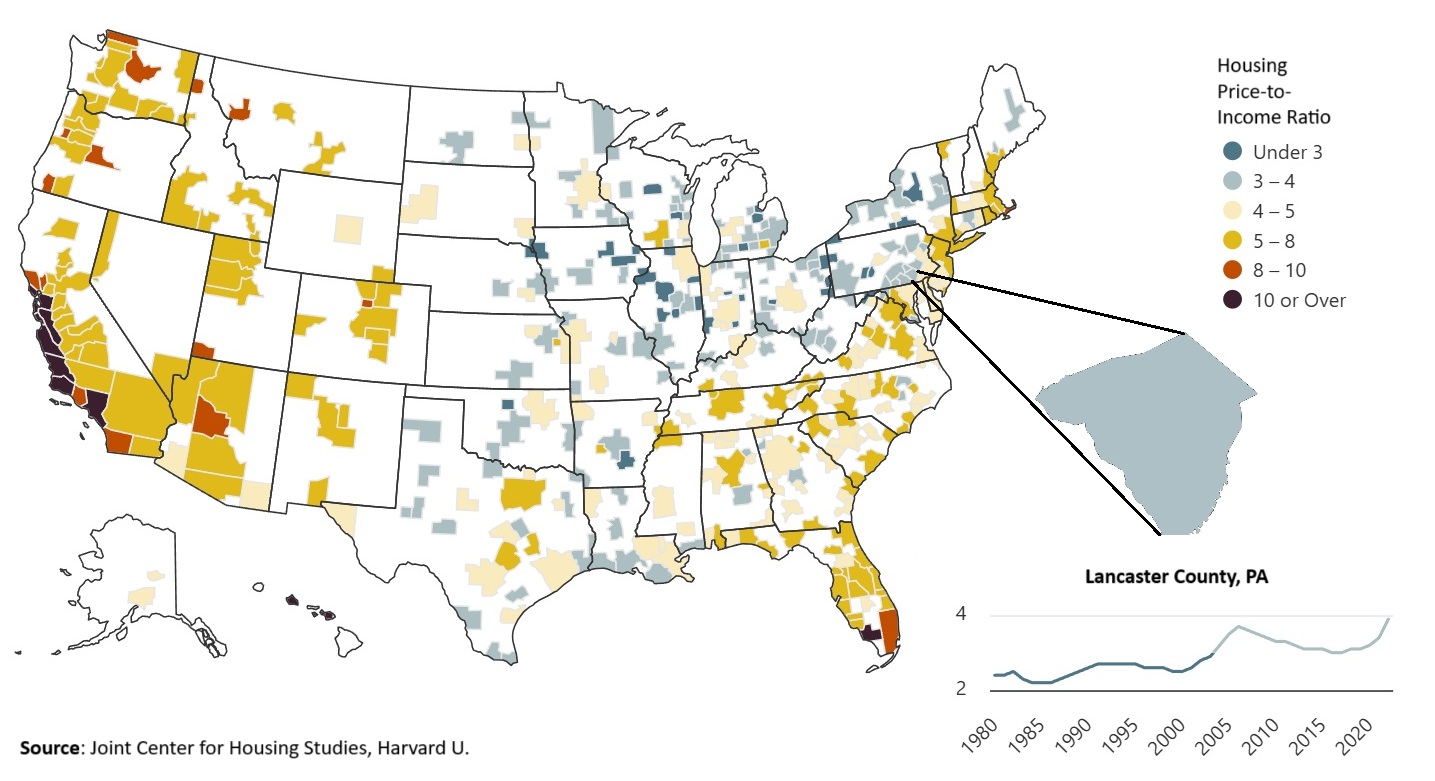

In January, the Lancaster County Homelessness Coalition tabulated 548 individuals in its annual “Point in Time Count,” or PIT count, a census of persons sleeping on the street or in temporary or transitional shelters. That’s the second highest number since 2012 and 70% more than the low of 321 achieved in 2017.

Outright homelessness is stressful and dangerous. Nationwide, death rates for homeless individuals are about 3.5 times higher than among comparable housed populations.

Outright homelessness is stressful and dangerous. Nationwide, death rates for homeless individuals are about 3.5 times higher than among comparable housed populations.

Child homelessness

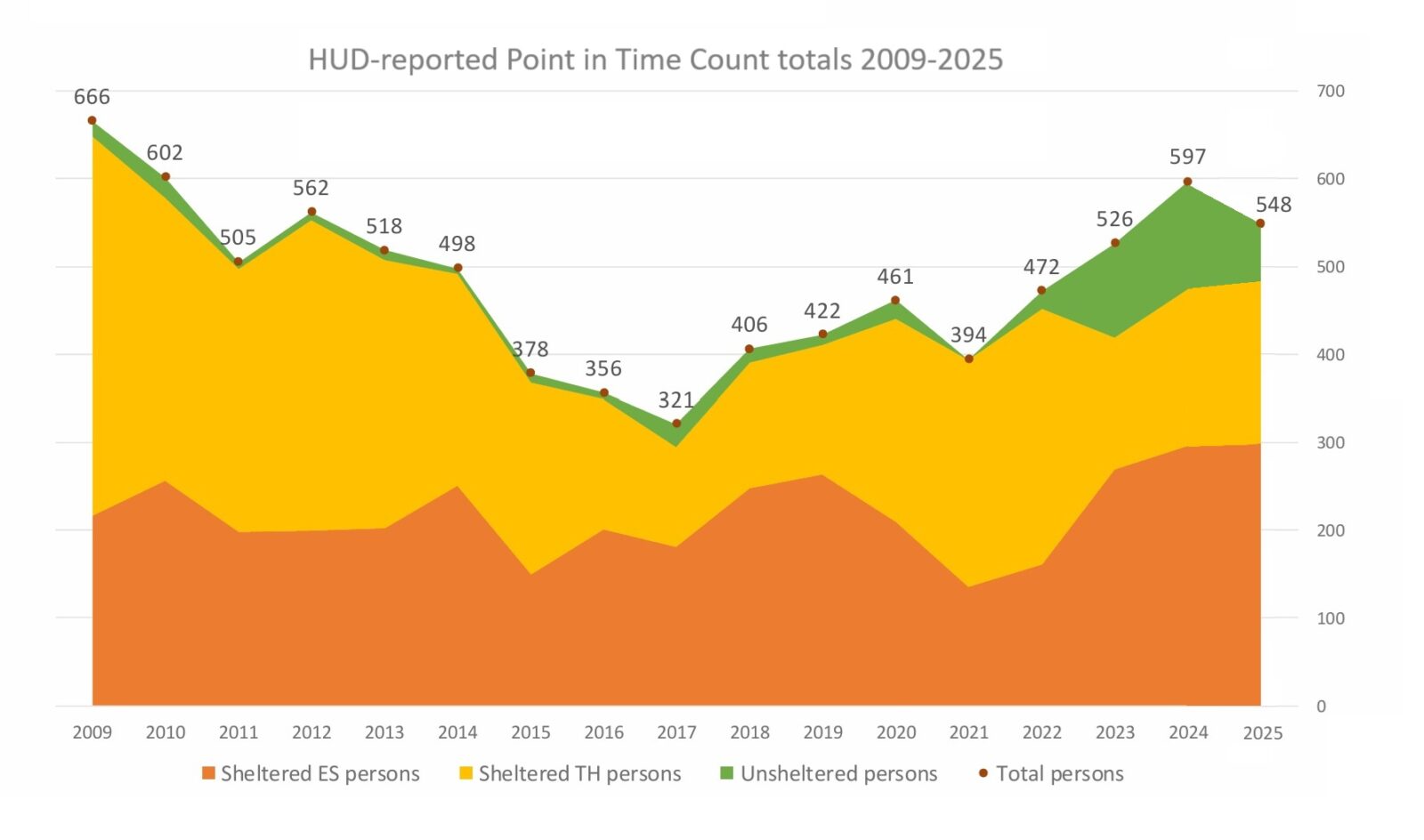

Lancaster County school districts identified nearly 2,300 homeless pupils in 2022-23. They are counted using a different standard than the PIT count, one that includes people living in hotels or doubling up with friends or relatives.

How would the HUD budget proposals affect housing here?

Federal funding is entwined with the local housing system to a far greater extent than people generally realize, with millions of dollars flowing into the county each year. Here’s some of what could change if it is curtailed.

Rental assistance

Federal voucher programs cover the difference between what low-income households can afford to pay (calculated as a percentage of their income) and their actual rent. The largest program is called “Housing Choice” (often known as “Section 8”); there are also various specialty vouchers. Federal funding also supports public housing operated by local housing authorities.

The administration’s proposal for HUD targets voucher programs for the sharpest funding decreases: They would be cut by $27 billion, or 43%. Instead of running the programs directly, the administration proposes creating block grants and handing administrative responsibilities over to the states. Assistance for able-bodied adults would be capped at two years. Funding for programs aimed at helping tenants achieve self-sufficiency would be ended.

Lancaster is home to both a city housing authority and a county one. The city authority administers 1,100 Housing Choice vouchers. The county authority administers a total of 1,009 vouchers: The majority are Housing Choice, while about one-quarter are specialized vouchers of one sort or another.

Between the two programs, HUD offsets more than $16.3 million a year in rent for low-income, senior and disabled county residents — more than $800 per household per month.

Additionally, the city authority owns and manages 469 public housing units at four locations. (A nonprofit affiliate, Partners With Purpose, owns another 95 “scattered site” properties.) HUD provides the authority an operating subsidy of about $1.3 million a year, plus about $1.5 million for renovation and capital expenditures.

Public housing tenants and voucher clients are “the working poor,” said Barbara Wilson, the city housing authority’s executive director. Most who are of working age have jobs, sometimes more than one. The remainder are elderly, disabled or both.

Without assistance, “where do these people go?” she asked. “What do they do?” If they’re supposed to earn more in order to afford market-rate rents, she asked, then how does eliminating self-sufficiency programs help?

And while rental assistance is a huge slice of the local housing authority’s budget, for the federal government, it is anything but, Wilson noted. HUD’s total funding accounts for just 4% of federal discretionary spending and 1% of total spending.

If the block-grant arrangement is implemented, she said, it will increase bureaucracy and paperwork. Pennsylvania’s government would have to build out a new system to manage and disburse housing authority funding, Wilson said, and if it chooses to do so via county governments, they would have to do the same.

The administration’s proposal would be destabilizing not only for tenants but for property owners, HDC MidAtlantic President & CEO Dana Hanchin said.

HDC operates 66 properties in three states, serving about 3,300 households. More than a third are in Lancaster County: 25 properties housing 1,300 households. Just over half of HDC’s tenants use vouchers to cover their rent.

Some HDC tenants stay a short while, others longer. Overall, the average tenure is four years, Hanchin said. They have access to a full range of resident services, including budgeting advice and resource navigation, to achieve financial stability and plan for the future.

“The housing is the foundation, but what you really want to do is help people succeed and thrive,” Hanchin said.

Affordable housing construction

To build housing for people of modest means, affordable housing developers need subsidies. Otherwise, their costs would exceed what their tenants could afford to pay.

The largest such subsidy is LIHTC (pronounced “LIE-tech”) — the federal low-income housing tax credit. Tax credits are offsets to an entity’s tax liability; developers can retain them or sell them to investors. Examples of LIHTC-funded projects in Lancaster County include Community Basics’ Saxony Ridge Apartments in Lititz and HDC’s Apartments at College Avenue in Lancaster.

Cuts to LIHTC do not appear to be in the works: On the contrary, the One Big Beautiful Bill passed by the U.S. House would increase allocations by 12.5%.

The problem, HDC’s Hanchin said, is that LIHTC doesn’t cover the full cost of a project. To cover the remainder while keeping costs down, developers usually tap other HUD funding streams, particularly Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) and HOME Investment Partnerships. HDC typically needs $1 million to $1.5 million from one or both programs, Hanchin said.

Both, however, are zeroed out in the administration’s budget plan. Without them, the numbers don’t work, Hanchin said. Private fundraising isn’t a feasible alternative: The amounts needed are too large.

“We need all the components to work together,” she said.

HDC MidAtlantic’s The Apartments at College Avenue near completion of Phase 1 of development. (Photo: Tim Stuhldreher)

Heather Valudes is the Lancaster Chamber’s president and CEO. The chamber recognizes the need for affordable workforce housing in its pro-business agenda. Moreover, Valudes noted, nonprofit housing development generates millions of dollars for the local economy. If organizations like HDC can’t move projects forward due to a lack of federal support, “the economy starts to look and feel different,” she said.

Homelessness and fair housing services

HUD dollars support a significant share of homelessness services in Lancaster County. CDBG and other federal funding streams help to pay for local shelters, including the new Clay Street site, seasonal shelters and day shelters. HUD underwrites “supportive” housing, which comes with services like counseling and training to help people transition to living independently. It funds temporary housing for domestic violence survivors. And it funds the services that connect people to the help they need, including street outreach and the United Way of Lancaster County’s 211 hotline.

Lastly, HUD funds fair housing programs, which support education and enforcement of anti-discrimination laws. Tenfold received $125,000 this year for fair housing education and mediation services.

The administration’s budget calls for consolidating a number of homelessness services into a single program, the Emergency Solutions Grant program, or ESG. Funding would be handed to states as a block grant to administer.

Overall, funding for services would be cut by $532 million, or 12%. As noted before, the CDBG program is slated for elimination; fair housing and housing counseling programs would be zeroed out, too.

Losing the CDBG program would be a blow, Thorsen said. It’s flexible funding, and enables communities to tailor services to local needs.

Channeling funding through ESG, he said, raises concerns about permanent supportive housing, which helps people with documented barriers to achieving self-sufficiency. Lancaster County has more than 150 permanent supportive housing beds; more than 60% of them depend on HUD funding, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Under current law, permanent supportive housing cannot be funded using ESG. That could change through the proposed consolidation, but if not, such services “would effectively be eliminated,” Thorsen said.

Jeffrey, a U.S. Army veteran, and his son spent part of 2024 at TLC, Tenfold’s 52-room transitional shelter. There, case management and other services provided the support they needed to move into their own apartment. (Source: Tenfold)

As for fair housing, Tenfold would likely have to scale back its programs if federal funding is withdrawn, he said. In 2023-24, activities included multiple workshops, the distribution of more than 3,000 landlord-tenant fair housing guides and 19 landlord-tenant mediations.

OK, but what about the big picture? Aren’t subsidies and vouchers and so on wasteful and inefficient? Wouldn’t getting the government out of housing and promoting market-based solutions be better for everyone in the long run?

Everyone interviewed for this article acknowledged that the existing system has grave shortcomings and that reforms are warranted. But there’s a difference, agency leaders said, between strategic reform and just stripping away funding.

“It’s not what you do, it’s how you do it,” Wilson said. “Talk to us. Don’t just cut things.”

Critics often point to the much higher per-unit cost of building affordable housing versus conventional projects. Hanchin agreed that there are many ways in which the system could be streamlined and improved: “We’re very much open to figuring out how to make that happen.”

But that shouldn’t obscure the genuine need that’s out there, or the market failure driving it, she said. The fact is, as currently structured, the for-profit housing industry is chronically unable to serve a large swath of American households.

“The math doesn’t work,” she said.

The reasons are complicated. Regulation is partly to blame, ranging from national tariffs to zoning rules that put large swaths of land off limits to anything except single-family homes. Local municipalities impose numerous restrictions, all of which raise costs and lengthen the approval process. All told, the National Association of Home Builders estimated in 2021 that nearly a quarter of the price of an average home is due to government regulation.

None of that is going away any time soon. That means the alternative to subsidies is an even greater shortage of housing than exists now, Hanchin said.

Increasingly, people are realizing this is an issue that affects everyone, she said.

“At the end of the day, I think that people know that there are neighbors or friends or family who have struggled with housing instability or finding an affordable place to live.”

Federal Action, Local Impact

Connecting our shared community with accurate information about recent federal funding cuts by compiling stories and data from a variety of sources.

Continuum of Care & Homeless Outreach

Much of the U.S. Dept. of Housing & Urban Development goes to fund the local “Continuum of Care,” HUD’s term for the interrelated network of services provided to address local homelessness. Learn more about the services provided.