How Cuts to Federal Food Support are Impacting Lancaster County Residents

By Tim Stuhldreher in partnership with The Lancaster County Community Foundation

April 29, 2025

Our unique role as a community foundation allows us to hear directly from organizations on the front lines to learn first hand how federal initiatives are impacting us here in Lancaster County. To help connect our shared community with accurate information, we reached out to local organizations, leaders, and farmers to understand how cuts to federal food support is impacting residents throughout Lancaster County.

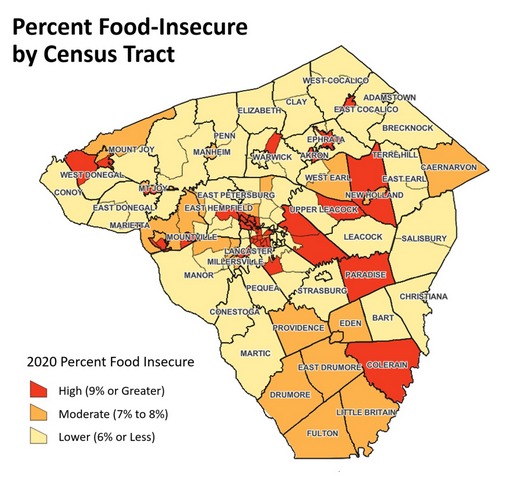

Is there a hunger problem in Lancaster County?

Yes, there is. An estimated 56,020 county residents, 10.3% of the population, are food insecure, according to the national nonprofit Feeding America. The figure is based on U.S. Census and U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

(Source: Lancaster County Hunger Mapping Report)

Food insecurity is higher for the county’s Black and Latino families, according to the 2023 Lancaster County Hunger Mapping report, a project of the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank. For children, the rate is higher still, the report found – about 50% above the county’s base rate.

Food insecurity is defined as the lack of access to enough food for a healthy and active life: It can manifest as families choosing less nutritious but cheaper food, eating less to stretch their budget or skipping meals altogether.

It can also manifest as outright hunger. In a survey of food pantry visitors conducted for the Hunger Mapping report, 44% of respondents said they have gone hungry. The survey found that 46% “cut back on food quantity and regularly did not eat enough food.”

Why are folks struggling? Isn’t the economy doing pretty well?

While unemployment is low and there have been wage gains, post-pandemic inflation and the region’s ongoing housing crunch have pushed costs sharply higher, leaving many working families worse off than before.

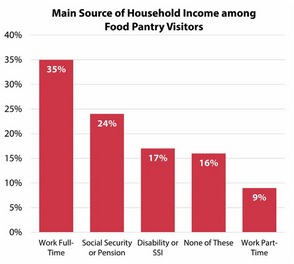

Income sources of food pantry visitors in Lancaster County (Source: Lancaster County Hunger Mapping Project)

The Central Pennsylvania Food Bank is serving more people now than it did at the height of the pandemic, CEO Joe Arthur said. In Lancaster County, its food went to 86,000 unique individuals in 2024, up 17% over 2023.

Other nonprofits say the same. Solanco Neighborhood Ministries moved to new quarters two years ago; since then, the number of families receiving food pantry orders has increased 29%, Director of Programming Todd Capitao said. At Power Packs, a nonprofit that provides weekend meal packages to school-aged children and their families in Lancaster, Lebanon and York counties, 2024-25 enrollment is up about 30% over 2023-24, Executive Director Brad Peterson said.

How are households being helped?

Food pantries and meal services all over the county are engaged in the mission of feeding their neighbors. The vast majority are churches and other faith-based organizations. Collectively, they provide tens of millions of pounds of food each year to needy households.

Crispus Attucks Community Center (Photo: Tim Stuhldreher)

The Central Pennsylvania Food Bank serves 27 counties and is the region’s largest charitable food distributor. Each month, it sends out more than $10.5 million in food: $1 million in its own purchases, $9.5 million in donated goods. In 2024, it provided 11.8 million pounds of food to more than 100 partner organizations in Lancaster County.

An even bigger role is played by the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, formerly known as food stamps.

As of March, 57,214 Lancaster County residents were enrolled in SNAP. They receive about $10.3 million a month in benefits — more than $120 million a year. Roughly 40% of recipients are under age 18.

SNAP provides nine meals for every one meal provided by food pantries. Importantly, it’s an economic stabilizer, allowing families to maintain purchasing power during recessions. The USDA estimates that every $1 in SNAP benefits generates $1.54 in economic impact.

Note that SNAP benefits work out to an average of $180 per person per month; many individuals receive less. The USDA estimates that even a “thrifty” family of four still needs to spend around $1,000 a month on food, or $250 per person.

SNAP has the potential to help even more Lancaster County residents than it does. The Hunger Map report found that more than one in six food pantry visitors had never applied for SNAP, and that more than four out of five would meet its income requirements.

What cuts to federal food support have been made so far?

The U.S. Department of Agriculture suspended the Local Food Purchase Assistance Program (LFPA) and its The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) has seen reductions in volume. Another program, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Emergency Food & Shelter Program (EFSP) has been paused. Here are details on each:

The Local Food Purchase Assistance Program (LFPA)

The LFPA provides funding through states for food banks to buy fresh food directly from farmers. It was especially successful in Pennsylvania: Over 2 1/2 years, it paid farmers more than $28 million for more than 25.9 million pounds of food. Nearly 190 farms and produce distributors participated. Of those, 17 were in Lancaster, including several co-ops representing dozens of small family farms.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture abruptly terminated the LFPA nationwide in early March, saying it “no longer effectuates agency priorities.” (It also canceled a related purchase program that provided food to schools.) In an appearance on Fox News a few days later, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins characterized the programs as “nonessential” Covid-era innovations and their continuation as “an effort by the left to continue spending taxpayer dollars.”

Joe Arthur, CEO, Central PA Food Bank (source: Pa.gov)

For the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank, the termination represents a loss of $120,000 a month, or 12% of its roughly $1 million monthly food purchase budget, CEO Joe Arthur said. In Lancaster County alone, the LFPA would have underwritten the purchase of 650,000 pounds of farm-fresh food over the next 14 months, about 6% of total inventory. (The dollar percentage is higher because LFPA food consists mostly of fresh items that cost more per unit of weight.)

“It’s a tremendous loss,” Arthur said.

The Food Bank is now paying for fresh goods to offset the loss of LFPA inventory. So are other organizations. The Community Action Partnership of Lancaster County is now buying fresh food itself for the 40 pantries it supplies to offset the loss of LFPA goods previously provided by the Food Bank, Director of Food Justice Amanda Frankeny said.

The Manheim Central Food Pantry receives inventory through both the Food Bank and CAP. Lately, due to the changes, “they don’t have as many choices as they used to,” pantry Chairwoman Cathy Knittle said, so “we’re buying more with our funds.”

Pennsylvania is challenging the cancellation as illegal and urging the USDA to reverse it. Gov. Josh Shapiro and Agriculture Secretary Russell Redding made the announcement March 25 at a roundtable at the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank’s Harrisburg headquarters. Redding sent a follow-up letter to Secretary Rollins on April 17, challenging statements Rollins made defending the cancellation during an appearance in Lebanon County.

The loss has been a blow for local farmers. For Sunny Harvest, a cooperative wholesaler in southern Lancaster County, LFPA accounted for about one-sixth of its business, Manager Ephraim Esh estimated.

Sunny Harvest sources produce and eggs from some two dozen Amish farms. At its peak, it was sending six pallets a week to the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank, Esh said, and four times that amount, 24 pallets a week, to Philabundance, a food bank in Philadelphia.

His team is trying to find other customers, but it’s challenging. Asked if Sunny Harvest would like to see the purchase program reinstated, he said: “That’s what we would hope. We certainly would.”

The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP)

Through TEFAP, the USDA buys food directly from farmers for distribution to food banks. States receive allotments based on poverty and unemployment data.

Since March, food banks nationwide have been reporting reductions in TEFAP shipments, often without advance notice. So far, 11 truckloads scheduled for the Food Bank have been canceled, Arthur said. It’s projecting a loss of 200,000 pounds of food through mid-2026 in Lancaster County alone, or about 2% of its annual shipments.

The Community Action Partnership received and distributed 880,000 pounds of food through TEFAP last year, said Julie Rhoads, CAP’s vice president of health and nutrition. It has been seeing less inventory in the program over the past few months, but has not received any direct communication from the USDA about reductions, she said.

The Emergency Food & Shelter Program (EFSP)

EFSP provides funding for homelessness services, including meals for homeless and housing-insecure individuals. Lancaster County normally receives about $200,000 a year. In January, the program was paused and its future is unclear.

To tide over agencies that rely on EFSP, United Way of Lancaster County has established a Food & Shelter Fund, seeded with an initial United Way contribution of $150,000.

“While the federal landscape is uncertain, we are committed to ensuring our resources are directed where they are needed most,” United Way President Kate Zimmerman said in a statement.

Power Packs receives about $10,000 in EFSP through Lebanon County. It’s only about 5% of the nonprofit’s budget, but “every dollar really counts,” Executive Director Brad Peterson said, adding that Power Packs is seeking to make up the difference through private donations.

What other cuts might be coming?

By far the No. 1 concern is the possibility of significant eligibility or benefit cuts to SNAP, Food Bank CEO Arthur said. If that happens, food pantries could find themselves overwhelmed by a flood of new clients.

Assisted by volunteers, neighbors make their way through the food pantry at Crispus Attucks Community Center on Wednesday, April 23, 2024. (Photo: Tim Stuhldreher)

Any reductions or cost-shifts for SNAP “would really be disruptive,” Rhoads, of CAP, said.

Advocates for social services are alarmed because of the budget framework recently passed by Congress. It calls for $230 billion in cuts to agriculture programs over the next 10 years. (They say Medicare and Medicaid are at risk too, due to the $880 billion in cuts it demands from the Energy Commerce Committee, which oversees the two health programs).

U.S. Rep. Glenn Thompson, R-Pa., heads the U.S. House Agriculture Committee. At an appearance in Lebanon County with U.S. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins earlier this month, he insisted that no cuts to SNAP benefits are envisioned.

Analysts are skeptical. “It is mathematically possible to leave SNAP untouched — but it would require cutting everything else the (agriculture) committee oversees, on average, by 75%,” Bobby Kogan, senior director of federal budget policy at the left-leaning Center for American Progress, said in an op-ed.

Some observers think the plan may be to shift SNAP costs to the states. That would significantly impair the program’s operation, opponents say: States would have to come up with millions of dollars in new funding; moreover, their balanced-budget requirements would hamstring their ability to expand assistance during recessions — that’s when demand increases, but it’s also when their revenues typically fall, due to higher unemployment and lower business activity.

What else is in the budget framework?

Among other things, it includes extensions of the 2017 Trump tax cuts along with new tax reductions. All told, they would increase the deficit by roughly $6 trillion over the next decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office. About half the benefit would go to the richest 5%, according to The Century Foundation, citing an analysis by the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. (Update, 5/16: As of mid-May, the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation’s official estimate of the reconciliation bill’s revenue impact is that it would increase federal debt by $3.8 trillion. The independent Committee for a Responsible Budget, however, says the estimate relies on most new tax cuts only lasting through 2028. If they are extended, the deficit would rise to $5.3 trillion by 2034, and to $6.2 trillion if interest costs are counted.)

What’s the bottom line?

Working families have tight budgets with little or no margin, as do many retirees, CAP CEO Vanessa Philbert said. If their food costs go up, that’s less money for rent or utilities. The closer a family is to bare subsistence, the more likely it is that a small unexpected expense will tip them into a potentially catastrophic crisis.

Nonprofits, too, must constantly deal with tradeoffs and resource constraints. If SNAP is cut, Rhoads said, CAP can expect to see more demand for WIC, the Women, Infants & Children program. If charity food providers need more support from local donors, that makes it harder to free up resources for other worthy causes. Every change has consequences that ripple across the system.

Supporting healthy eating for everyone is a win for the community at large, Rhoads said. Well-fed children do better in school, boosting academic achievement and lifetime earnings. Good eating at all ages is protective of wellbeing. Bad eating habits, conversely, raise the risk of diabetes, heart disease and other ailments, raising healthcare costs in the long run.

“Diet is the cornerstone of health,” Rhoads said. If people can’t access good food, sooner or later “we’re going to bear those costs.”

Federal Action, Local Impact

Connecting our shared community with accurate information about recent federal funding cuts by compiling stories and data from a variety of sources.

Meet Malachi and Lori

Take a deeper dive into how federal funding cuts put local food access at risk by hearing directly from neighbors, Malachi and Lori.